To this day, I have a distinct memory of my mother locking the car doors when we pulled up to a specific corner in the downtown section of Michigan’s second largest city. It’s an intersection I’ve gone through many times in life – one of two necessary to get downtown. Also to this day, it has not been an intersection I’ve ever experienced any problems at. The only other noticeable attribute of this intersection and its surrounding neighborhood was that the people present walking in and out of nearby stores are almost exclusively Black. Not once did anyone ever try to open the car door or knock on the windows, so there wasn’t any plausible reason to think that someone might actually attempt something. Nonetheless, the unspoken corollary was, “There are lots of Black people downtown, and therefore when you are downtown, the doors must be locked.”

This kind of social stigma has only ever been reinforced by clues from popular culture that regularly place people of color in roles of thieves, violent criminals, and drug dealers. This pattern of racial criminalization and its consequences were summarized in a New York Times op-ed by Khalil Gibran Muhammad – Director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture – as,

…stigmatizing black people as dangerous, legitimizing or excusing white-on-black violence, conflating crime and poverty with blackness, and perpetuating punitive notions of “justice” — vigilante violence, stop-and-frisk racial profiling and mass incarceration — as the only legitimate responses.

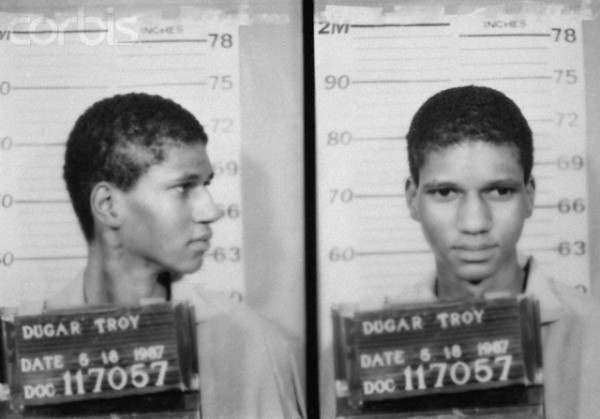

Mass incarceration is a serious issue. With the United States locking up more people than any other country in the world, it is not surprising that we have statistics that report Black or Latinos make up 70 percent of the students that are involved in school-related arrests or referred to law enforcement. When so many developing students essentially have that development taken from them when they enter the juvenile justice system, they cease to learn critical life skills like impulse control, teamwork, and interacting among peer groups. They leave the juvenile justice system behind their peers and this leads to a number of potentially lifelong setbacks, including a wage growth 21 percent slower than white ex-convicts. Incarceration is inhumane on a number of levels, but it also doesn’t work. With two-thirds of prisoners returning to prison in their life, the suspension of juvenile development creates a self-perpetuating cycle.

If ending the Prison Industrial Complex and mass incarceration is something you’re passionate about, there are a number of groups that are taking their own approach to combating this issue.

- The Animation Project uses digital animation technology to help continue adolescent development for teenagers involved with the juvenile justice system.

- Friends of the Children favors a social-worker approach, focusing on individual children deemed most “at-risk,” providing positive adult mentorship through graduation.

- The Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana works to transform the state’s juvenile justice system into one that builds on the strengths of young people, families, and communities to ensure children are given the greatest opportunities to grow and thrive.

- Books Through Bars sends quality reading material to prisoners and encourages creative dialogue on the criminal justice system, thereby educating those living inside and outside of prison walls.

- Common Justice offers an alternative to the traditional court process for youth charged with felonies such as assault, robbery, and burglary. Project staff bring together people immediately affected by a crime to acknowledge the harm done, address the needs of the harmed party, and agree on sanctions other than incarceration to hold the responsible party accountable. The project, based in Brooklyn, New York, seeks to repair harm, break cycles of violence, and decrease the system’s heavy reliance on incarceration.

by Rob Mooney

Lauren Silver

/ February 28, 2013The author’s anecdote is all too common–parents advising children to avoid “inner-city” or “rough” neighborhoods. The codification of this language reinforces the racial profiling and mass incarceration already embedded in the US Justice System. The range and reach of the organizations working to combat this issue is reassuring, in that the Prison Industrial Complex is becoming increasingly acknowledged.

LikeLike

Chaquenya Johnson

/ March 5, 2013I agree. The stigma attached to “black” people is so far embedded in the history of the country that it is clearly reflected in the demographics of prisons. As more money is being invested in building prisons, more minorities are incarcerated and fewer funds are allocated for reconstructing neighborhoods in need along with investments being made into programs for then minority that may indeed uplift the communities of minorities. Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis does a good job of depicting how rapid prisons are being built.

LikeLike

Talia Pedraza Avila

/ May 14, 2013Great resources for further research on the topic. I’ve been doing some research on Angela Davis’ and Johnny Cash’s advocacy against the prison system in the U.S. And I was shocked by the idea that more black men are imprisoned today than there were enslaved in 1850. I recommend reading: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/10/12/michelle-alexander-more-black-men-in-prison-slaves-1850_n_1007368.html

LikeLike